Chapter One

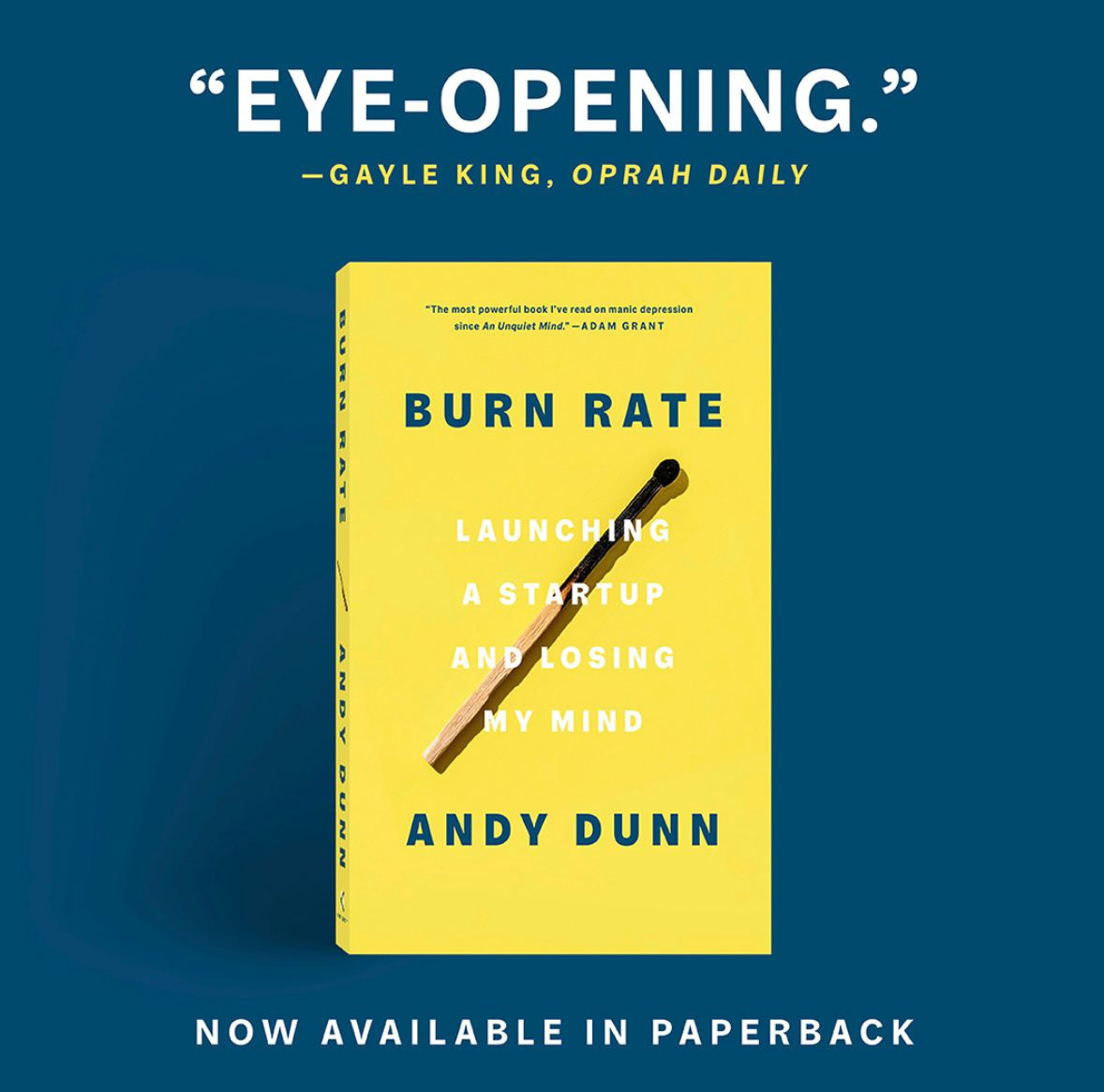

The Burn Rate paperback drops today. Here's how it starts.

In early 2022, while Burn Rate awaited publication, my editor sprung an eye-opening tidbit on me: most books never make paperback.

It lodged in my brain.

What if this is an epic fail? What if it never lives on in print?

I feel lucky to say that today our paperback is live, with a new afterword shared in Inc. this morning.

That afterword is how it ends.

Here’s how it begins.

In Hindi, there are at least ten words for “aunt” or “uncle.” Your mother’s sister, mother’s brother, father’s sister, father’s brother, mother’s sister-in-law, mother’s brother-in-law, and on and on: they all have different names. The most affectionate term of all is masi, reserved for your mother’s sister. For my sister and me, our mom’s family was the strongest force in our childhood. Our mom has four sisters, so I have four masis; it was a profoundly and proudly matriarchal upbringing. What I didn’t know at the time was that I would one day spend thirteen years building a company named for a species of matriarchal chimpanzee.

Mom’s parents, Prakash and Dhian, were born in Rawalpindi, a city in Punjab State. In 1947, the British split Punjab in two, creating a Pakistani side and an Indian side: Muslims over here, Hindus over there. My grandparents, a Hindu and a Sikh, had to leave in the middle of the night with their two daughters. The region was thrown into chaos, with an estimated fifteen million people displaced, and at least one million killed.

Usha Ahuja, my mother, was born in this context, in a refugee town called Kurukshetra, during her family’s multiyear journey from Rawalpindi to New Delhi, where they eventually settled. My mom’s mom, our Badi Mummy (Prakash), was a child bride, not educated beyond the sixth grade. She lost two children in infancy before she turned eighteen. Then she had seven kids: five girls and two boys.

My mom and her sisters adored their father, and they feared him, too. The level of his expectations for their success was daunting. He was an enterprising building contractor, a chain smoker, and an alcoholic. He instilled in his daughters a progressive message, ahead of its time in 1950s and ’60s India: “You don’t want to be dependent on a man like me.” His vision for his children was for them to get educated and make it to the United States. By the time he fell ill with emphysema, my mom had graduated college and been shipped first to Canada and then to the United States, to live with my Ashi Masi, by then an obstetrician-gynecologist. My aunt would go on to deliver both my sister and me.

My mom’s mandate was to get trained as an X-ray tech and send money home, living with her sister so that she could pass on 100 percent of her income. With her father ill, they desperately needed the money, and my mom—a most dutiful human—answered the call to the sublimation of her own possibilities. Any dreams she had of becoming a doctor, like two of her older sisters, were subsumed by that short-term need in the late 1960s. She never complained about it. She never complains. Money was so tight that when my grandfather died, in January 1969, my mom couldn’t afford to go home to New Delhi for his cremation. It haunts her still. She has never gotten closure.

Mom’s sisters built the clichéd Indian-American immigrant family, filled with doctors and married to them, too. Ashi Masi’s husband is a radiation oncologist; Shano Masi, an internal medicine physician, married a surgeon; and Dolly Masi, my mom’s younger sister, is a physical therapist. My dad’s side of the family is smaller, but also filled with medical professionals.

As I was growing up, doctors were everywhere. It’s a marvel that, when the time came, we were all in denial. My older sister, Monica, and I felt invincible—there was always medical help ready for any issue we faced.

Except, of course, for the one that came.

From "Burn Rate" by Andy Dunn. Copyright 2022 by Andy Dunn. Excerpted by permission of Currency, an imprint of Crown, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.