Name Your Enemy

The late great Joel Peterson used to tell us at Stanford that sometimes it’s good to have an enemy.

He’d talk about Pepsi’s two-word strategy back in the day:

Beat Coke.

I never asked Joel for the backstory while he was here. Which I regret. So I looked it up.

In the 1950s, when Coca-Cola was dominant and Pepsi was one of dozens of competitors, a CEO named Alfred Steele took over. Over a five-year span, Pepsi’s net earnings increased roughly 11-fold, while Coke’s grew far more modestly.

Under his leadership, Pepsi repositioned itself away from being the “cheap alternative,” focused on quality over quantity, expanded globally, modernized distribution, and invested heavily in brand and advertising. By the late 1950s, Pepsi wasn’t just alive — it was Coke’s primary competitor.

Steele in fact explicitly defined the strategy as “Beat Coke.”

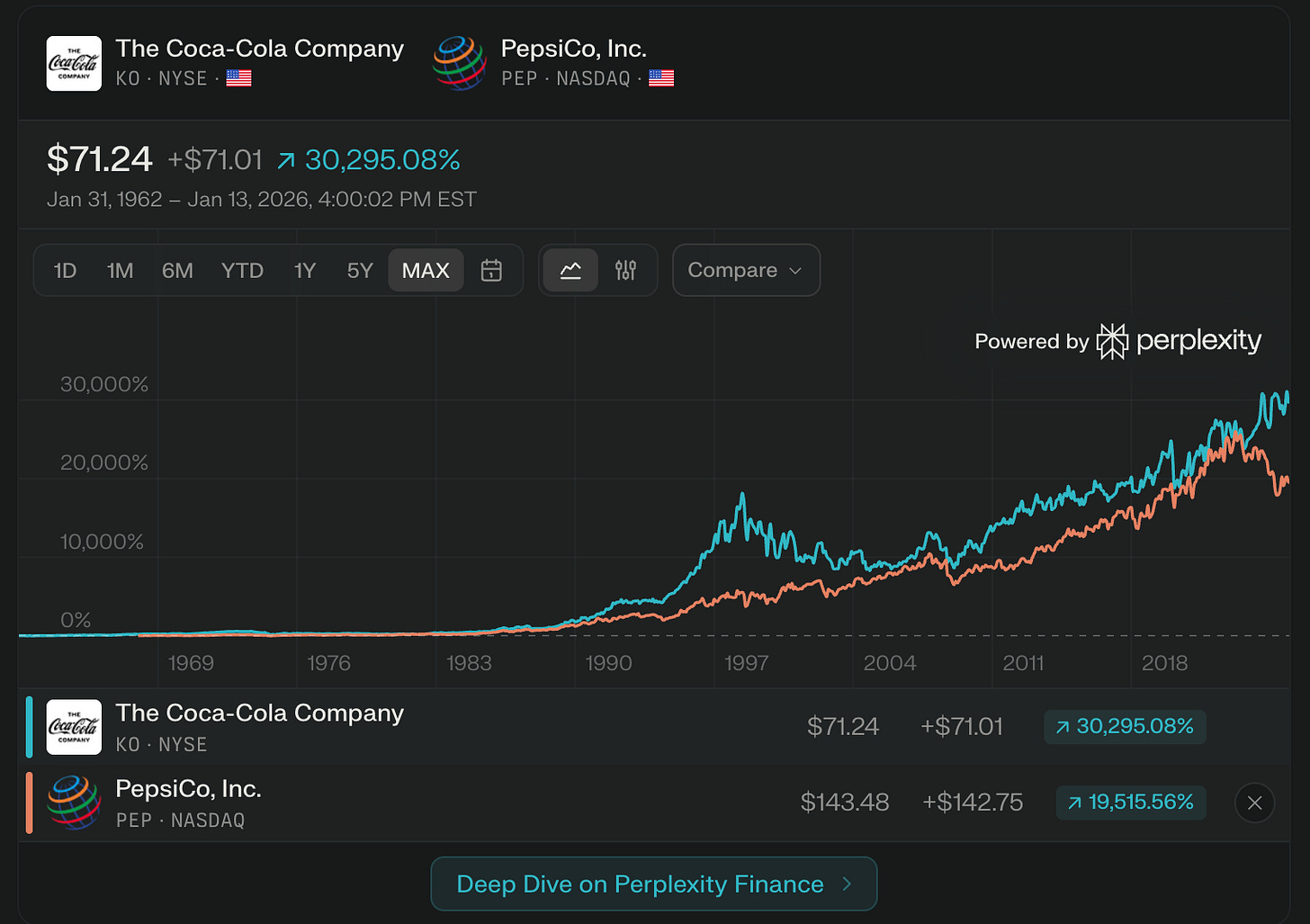

Today, Coke’s market cap is roughly $300B and Pepsi’s is around $200B. Pepsi never became the enduring #1. But by naming its enemy, it went from one of many to the clear #2, and at times, nearly at parity.

What’s interesting is that Steele did two things at once: he openly framed Coke as the benchmark to beat, while also redefining the competitive set by saying Pepsi’s real competition included coffee and tea. He narrowed the mission and expanded the vision.

That’s the lesson.

Naming an enemy isn’t about ill will. It’s about framing an audacious goal in a way that’s simple, concrete, motivating, and easy to measure.

I’m a sports fan, and I’ve been trying to understand how Curt Cignetti transformed Indiana football and how Ben Johnson has begun reshaping the culture of the Bears—both in a remarkably short time.

They did many things right. But one thing that stands out: they named their enemy from the jump.

When Ben Johnson took the Bears job, he didn’t talk in abstractions. He named the Green Bay Packers as the enemy to defeat. The oldest rivalry in football. The team that had dominated Chicago for decades. He didn’t hedge. He didn’t soften it.

He openly taunted them. Notice the way he sets it up. Notice the way he chooses his words. He rehearsed the moment.

And then, in the most improbable of ways, it started to come true. The Bears beat the Packers twice this year, and knocked them out of the playoffs.

Cignetti did something similar at Indiana. At a pep rally, he went after Purdue first. Then he raised the bar further — calling out programs IU almost never beats—Michigan and Ohio State. It was trash talk, yes, but it was also deeply intentional.

On a recent episode of 60 Minutes, Cignetti explained why he did it. Naming the enemy wasn’t about bravado. It was about inspiration and belief. About making the goal explicit enough that people could get fired up by knowing their leader thinks it’s achievable.

Head to the eight minute mark and check out the unexpected reason he did it.

What fascinates me is that once you name this specific objective — and then actually follow through — something powerful happens.

Your words start to matter.

People believe the next thing you say because the last thing came true. And the last thing came true because you said it would.

You named the enemy.

And then you beat them.

Founders: take note.